We tend to divide people into introverts and extroverts. At a first glance, we’re inclined to label shy and quiet people as introverts and the talkative and charming ones as extroverts. In reality, the distinction between these two types of personalities is not so clear-cut. In her book entitled The Hidden Gifts of the Introverted Child Dr. Marti Olsen Laney explains that:

“Introversion and extroversion are not black and white. No one is completely one way or another — we all must function at times on either side of the continuum”

But why do people who are considered more introverted tend to be less talkative than extroverts?

That’s the question that’s been on my mind for some time now. So let’s find out what the science says about the introverts’ preference to choose quiet settings instead of making speeches in front of the crowds.

Words don’t come easy to introverts

Introverts are often seen as people who don’t like to talk to others, especially to strangers. Some people can even consider them unfriendly or big-headed. That’s the biggest bias that harms those less talkative because sometimes the reverse is true. The contrast between those two types of personalities is caused by the differences between the brains of introverts and those of extroverts.

When you ask an introvert any open-ended or personal question, such as “What do you think about XYZ?” or “What is your hobby?”, chances are high that there will be a long awkward pause or you will just get a short and simple answer. One reason for that may be the way introverts process information. It’s simply a more complex mechanism than in extroverts.

Introverts rely chiefly on long-term memory

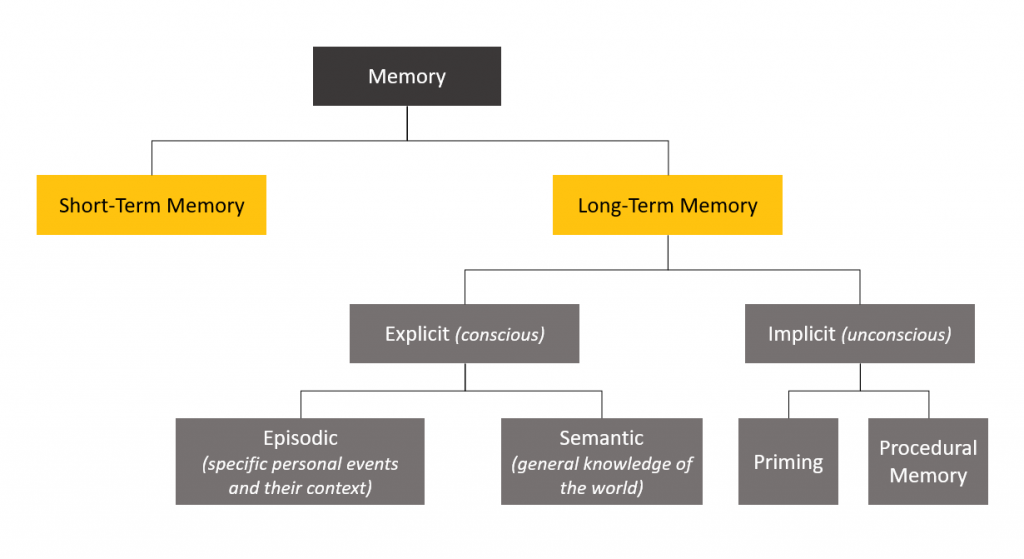

Let’s start by explaining the differences between long-term and short-term memory. We all have both of them, yet they serve different purposes. Long-term memory, as the name implies, is responsible for keeping information for a long period of time. That’s a fine human feature but it has some drawbacks. Retrieving such data is a more complex process so it takes time. When you listen to the music that you were listening in your childhood or when you taste a cake that you loved when you were in kindergarten, you use the power of long-term memory.

On the other hand, short-term memory (also called working memory) stores less information for a shorter period of time. Working memory is responsible for putting information to be used in a quick response, such as to answer an unexpected question. It’s helpful because it’s fast and easy to access in comparison to long-term memory.

In the book entitled The Introvert Advantage [1] Dr Laney confirms that introverts favor long-term memory over short-term memory.

While creating sentences they want to communicate, they utilize information stored in long-term memory, which is a lengthy and complex process. That can explain why introverts need more time to think about what they want to say. It is actually what makes them great experts because they can be perceived as more precise and concise. It is important to them that each word adds value to what they say. They just hate lengthy and vague speeches.

That’s the opposite to the way extroverts use their memory. They favor short-term memory, thanks to which they are able to generate responses much more quickly and use plenty of words in their sentences. That’s probably the reason why it’s easier for extroverts to speak at conferences and answer unexpected questions from the audience. They can just create answers faster than introverts.

Introversion, shyness and anxiety

Let’s make it clear, not every introvert is anxious and not every anxious person is an introvert. But there is some common ground for introversion, shyness and anxiety. Introverts can experience a bit of anxiety when they need to speak in social situations. Introducing themselves, talking to a stranger or public speaking are mentally draining for them. These are the examples of a definitely stressful situation out of their comfort zone.

Being exposed to a stressful situation makes it even harder for them to think, focus and speak. During times of anxiety, a stress hormone called cortisol is released. And according to a study [2] conducted by Mathias Luethi, Beat Meier and Carmen Sandi, cortisol negatively affects our memory and concentration:

“These results reinforce the view that acute stress can be highly disruptive for working memory processing.”

Different neural pathways

For many introverts writing is easier than speaking. That’s why they prefer texting and emailing to talking on the phone. According to Dr Marti Olsen Laney, writing involves different neural pathways than speaking [1].

I’ve already mentioned in one of my previous articles that extroverts need less time to process information that comes to their minds than introverts. Images, sounds, smells and other stimuli reaching an extrovert’s brain travel through a shorter neural path. As a result, extroverts need to spend less time analyzing information. In the case of introverts the same data runs through more areas, including those associated with long-term memory and planning.

Conclusion

In our extroverted world, where we favor people who are social, open and talkative, you need to remember that there are others, meaning those who prefer quiet settings rather than large social gatherings.

If they use less words or need more time to think before saying something, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are unfriendly or they lack the knowledge on a particular subject. Maybe it’s simply because they have a different personality which makes them process information in another way.

Neither worse or better, just different. It’s this diversity that makes us beautiful and interesting. After all, if everyone was the same, the world would be a boring place.

References

[1] Marti Olsen Laney. (2002). The Introvert Advantage: How to Thrive in an Extrovert World. Workman Publishing Company.

[2] Lüthi, Mathias & Meier, Beat & Sandi, Carmen. (2008). Stress Effects on Working Memory, Explicit Memory, and Implicit Memory for Neutral and Emotional Stimuli in Healthy Men. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2. 5. 10.3389/neuro.08.005.2008.