Succumbing to distraction

One of the biggest problems of working from home is being exposed to a lot of distractions. Pets, crying children, TV, fridge and all the other things are just waiting to steal your attention. Distractions didn’t just appear when we started working from home. They were already there before, in our offices. I bet you had a colleague swing by your desk to ask you just a quick question or for a small chit-chat or to arrange a bunch of unnecessary ad-hoc meetings more than once. And even if you didn’t have such distractions, because you created your own oasis filled with peace and quiet, in time, your biggest enemy arrived anyway. Technology. Every day you receive plenty of notifications from various apps. There is a colleague who sent you a message. You just got an invitation to a meeting. An important email is waiting in your inbox. Your subscription to a learning platform is about to expire. In those circumstances, when do you actually have the time to do your work?

This problem of living in a world of constant distraction has become the subject of an increasing interest to scientists. A psychology researcher and the author of a book entitled, “Indistractable” [1], Nir Eyal, who studies human behavior around technology, says that:

“The most important skill of the future is being ‘indistractable.’

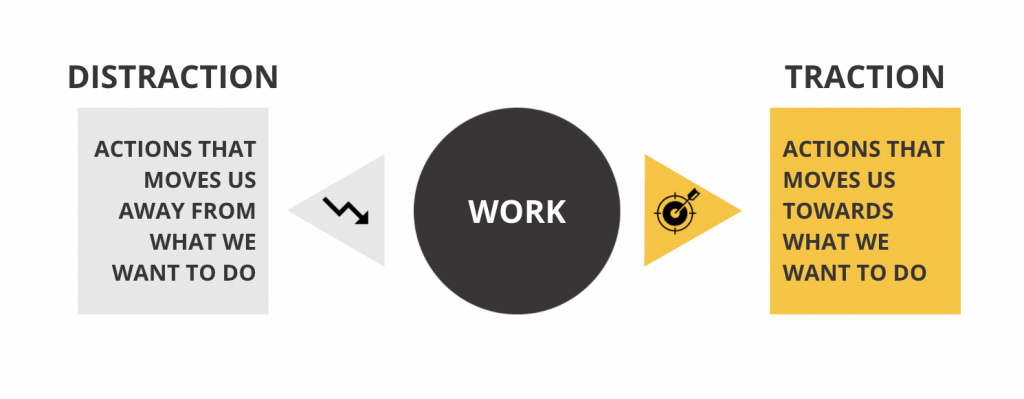

Eyal describes that the opposite of distraction is not focus. It’s something that he calls traction. It’s not enough to stay focused because being focused on something doesn’t necessarily move us towards achieving our goals. There is a huge difference between spending 30 minutes on a task and making progress within the same period of time.

Let’s be honest, bouncing between pointless meetings and chat notifications won’t help you stay focused and lead to fruitful results. Especially, if your job requires you to be creative and solve problems in an unconventional way. Having too much on your hands is a mark of busyness, not productivity. So, what is the solution to that problem?

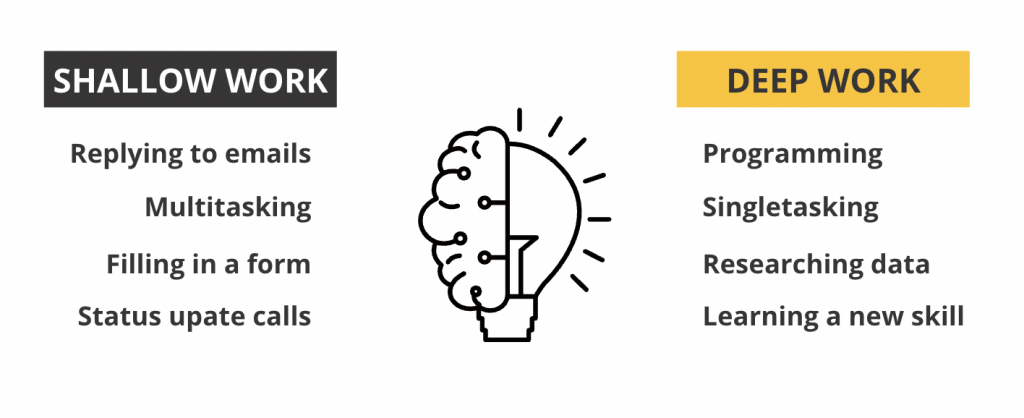

Deep work. This concept was introduced in one of the blog posts by Cal Newport, an author and computer science professor at Georgetown University. Later on, it was also mentioned in his bestselling book entitled “Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World”. Deep work is a mixture of understanding how you work best, removing distractions from your environment, planning and protecting your deep working time, and then just practicing good self-discipline in order to actually deliver what you promised to in that time.

The concept differentiates between two types of work: deep work, which consists of activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limits, and shallow work, which is related to not cognitively intensive tasks that are of low-value and easy to replicate, like responding to emails, scanning websites, and using social media. Shallow work results in people spending huge amounts of their day switching contexts, which reduces their ability to perform at their cognitive peak.

Let’s be clear, deep work is not a new concept. It has a lot in common with the concept of flow states. I’m going to devote a separate article to the concept of deep work, but long story short, its main part consists of planning and structuring time. Newport says that the prerequisite to deep work is to create an isolated space for deep working, free from emails, phones, and people. And, last but not least, it’s about practicing good self-discipline in order to actually do what you set out to do in a particular period of time. Some degree of isolation is healthy and useful for your work.

Using meetings to postpone making a decision

People in an office tend to meet a lot for plenty of reasons. To share their thoughts, discuss issues or solve problems. But organizing meetings is not always a good idea. I observed the tendency for some people to schedule meetings, because they just want to talk instead of making decisions. It’s much easier to gather people around and talk about a problem rather than to take responsibility for an action.

Some time ago, I actually witnessed such a situation at work. A team was meeting over and over again just to talk about a problem. They wanted to choose which tool they should use to share their knowledge. And in order to make a decision about it, they kept scheduling one meeting after another. I realized that they would spend a lot of time on it without making any decisions. They thought that they would finally make a choice at “the next meeting”. But first, they needed to schedule another meeting. They couldn’t make a decision even after four sessions. Yet, it doesn’t make sense to get together if there are no actions taken and no one takes responsibility for the outcome.

This tendency seems to be even more dangerous in remote settings. How many times should you meet and discuss things together before you take a meaningful action? Far too often, meetings are used as mechanisms to force people to carve out the time to think about something that seems important. We tend to set up meetings so that we can have the time to think together or we call a meeting to force our colleagues to spend some time thinking about a particular matter. Unfortunately, a group gathering is not the best way to start thinking about problems and solutions. Meetings are the most effective when people have done the hard thinking ahead of time. When they did some preliminary work beforehand.

Not trusting the team members’ intentions

I work hard and try not to slack off. I believe in the idea of deep work, and controlling my productivity is one of my biggest goals at work. But even if I worked for 8 hours without any breaks, doing my best, I would be frightened if someone could just log in and see what was on my screen. I know how it feels. I was in a similar situation as a developer in one of the companies I worked for. An old-fashioned, traditional manager liked to hover around software engineers and look at their screens. He would just look over their shoulders with a poker face pretending to understand what they were doing without making any comments. Maybe it wasn’t his intention to control his team. Maybe he just wanted to be closer to his teammates. But believe me, even if you were working hard, the idea of having your supervisor peer behind your back was kind of a mortifying experience and nobody enjoyed it.

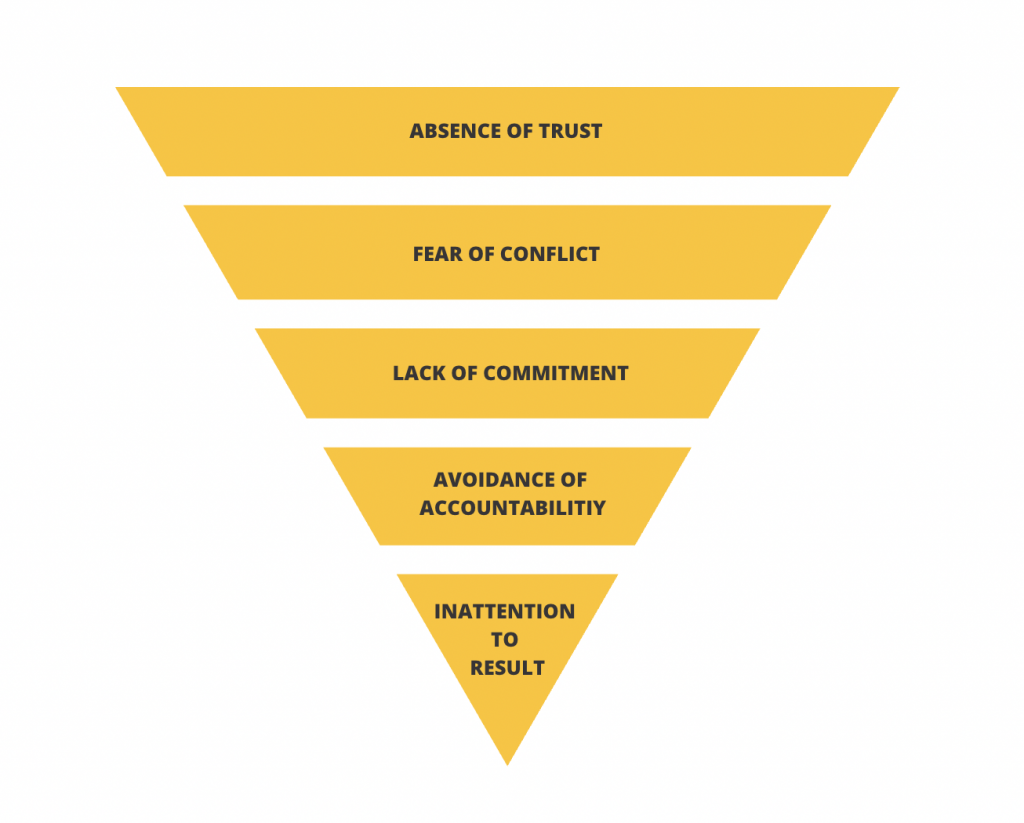

And yet, many managers, whose team members work from home, feel the need to check up on people. I’ve even heard about companies installing applications that randomly screenshot their workers’ desktops to make sure they’re not slacking off. What an idea?! As a manager, if you feel the need to create such a surveillance system, then you have trust issues. And there are two types of trust that you can miss.

The first one, according to Patrick Lencioni [2], is the lack of trust in people’s skills. That’s typical for technical managers who don’t believe in the technical skills of their subordinates, e.g. other software engineers. They always need to double check every little piece of code, which takes a lot of their time. But isn’t that a matter of not hiring the right people who perform well?

And right now, while working remotely, we can also notice the lack of trust in terms of people’s intentions. This is the basic type of trust, and without it it’s not possible to build the other ones. How can you verify if someone is actually working at the moment? The hard truth about trust is you have to show it to get it. With remote work, we’re in many ways forced to let go and show a little more trust. But, of course, it doesn’t mean that you need to abandon all the rules and policies meant to prevent people from abusing their company. Treat people like adults and see what happens.

Understanding remote work flexibility incorrectly

Lately, I have been part of a challenging discussion with one of my teammates. He didn’t show up to meetings, because it was ruining his flexible style of working. For the same reason, he also started work at different times. Sometimes he began at 8 a.m., other times, at 11 a.m. Without notifying anyone about it. It wouldn’t have been a big issue if he wasn’t part of a team and we all didn’t need to collaborate with him to achieve a common goal. Teamwork is not about delivering tasks by each teammate, but about collaboration and communication. His argument was that there was nothing wrong with his approach, because remote work is all about flexibility. That made me realize how people misunderstand the flexibility of remote work.

Flexibility does not equal having no structure at all. If you are part of a team, you need to obey some basic rules, e.g. what the core hours of a team are, so you know when to plan collective meetings. The same applies to documenting different aspects of work. I know that nowadays so many “agile” people say that in “agile” there is no documentation. But that is obviously not true. It’s a misinterpretation of the agile manifesto, which stands for:

“Working software over comprehensive documentation”.

But it doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be any documentation. What is the link to a business process description? Where is the template for a company presentation? One of the most common flaws of remote teams is not documenting things or not keeping them up to date. We have meetings and don’t document what happened in them. We make decisions and don’t record them. We make changes to things and tell just a few people about it. Working remotely can give you an excuse to establish a shared set of rules. But beware, this leads to chaos, not flexibility, and chaos is counterproductive.

References

[1] Nir Eyal. (2019). Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life. BenBella Books.

[2] Patrick Lencioni. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable. Jossey-Bass.