We’re generally not good at spotting lies

Let’s agree, people fail to spot lies. Studies [1] have shown that an average adult can distinguish fabrications from the truth only 54% of the time. That’s almost as good as a blind guess. It means that an average adult is not very skilled in lie detection.

A team of scientists led by Marc-Andre Reinhard found [2] that experience doesn’t necessarily help us detect deceptions in an employment interview. The experienced employers weren’t actually better at spotting dishonest candidates than their less experienced colleagues. The reason for that is what psychologist call truth bias. As human beings we are hardwired to assume that what we hear and what we see is true.

If that wasn’t enough, the tendency is that the more confident we are about our ability to spot a lie, the worse we actually are at it [3]. The only way to improve lie detection skills is to understand what the correct indicators of a lie are. Marc-Andre Reinhard demonstrated [2] that having correcting beliefs about indicators led to more developed lie detection abilities. In this article I will present the common signs of deception that will make you a better liespotter.

Stonewalling

Stonewalling occurs when a person withdraws from a conversation and avoids answering the question entirely. A person may ignore your question and keep talking about something else or respond with a deprecating remark. In most cases, the goal is to avoid answering the question or create a delay to buy some time.

There are many approaches to stonewalling. An interviewee can give you a vague response that doesn’t bring anything to the table or he may completely refuse to answer by diminishing the value of the question. He may even criticize your question or respond to a question with a question, which is considered not very polite, not to mention annoying.

Some people use stonewalling unconsciously because of increased adrenaline due to an increase in stress. This is our fight or flight response to a dangerous situation and it’s a great example of a defense mechanism for self-preservation or safeguarding your emotions [3].

When you ask a question and an interviewee rolls his eyes, trying to prove this question irrelevant, it is a big warning sign. It’s hard to say whether that person is definitely lying or simply rude but trying to shut down a conversation before it’s begun should make you more cautious. Remember, aggression in form of words or facial expressions is one of the indicators of deception.

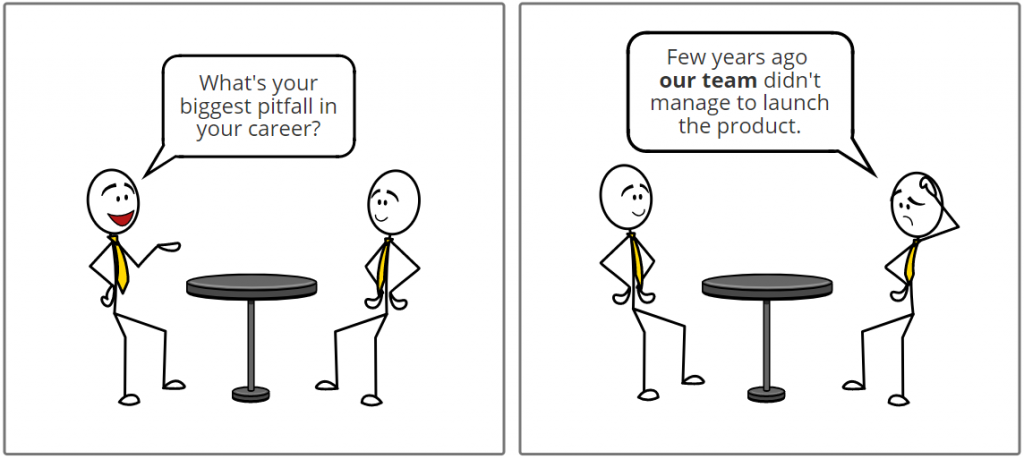

It’s about the “we” instead of the “I”

That is one method of distancing yourself from the truth. Liars want to remove themselves from the story which can be damaging to their reputation. They tend to avoid using pronouns like “I”, “my” or “mine” in order to feel more secure and stay further away from the real problem.

When asked about the biggest pitfalls liars prefer to disassociate themselves from the situation and stand on the sideline. That’s why they express themselves using words like “we” or “our team”. It’s more comfortable to talk about the group of people instead of yourself. They don’t want to take responsibility for poor decisions.

They also prefer to use passive form. Liars would rather say “the product launch was postponed“ instead of “I postponed the product launch”. Such linguistic methods are used by liars to avoid consequences and to save their image.

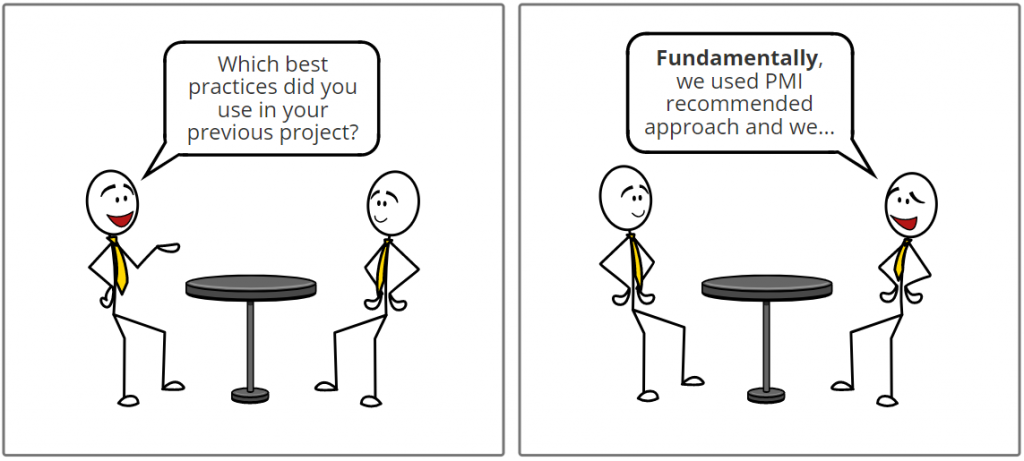

Exclusionary qualifiers

Susan Carnicero, the author of Spy the Lie [4] and former CIA agent, pointed out that liars tend to use exclusionary qualifiers: “not really”, “in general”, “fundamentally”, “mostly” or “for the most part” before giving an answer in order to give it more latitude. By using that technique liars are able to tell the truth but not the whole truth. It lets them maintain the illusion of truth to sound credible.

What does “fundamentally” mean in that scenario? Does it mean that you do know what the best practices are but you didn’t use all of them? Or maybe there is a specific bad practice that you’re not proud of and you don’t want to talk about?

Sometimes using such qualifiers may be harmless and it’s simply an element of someone’s speaking habits. But you should pay attention to it and consider it a warning sign. The good news is that as an interviewer you can easily handle such a situation. All you need to do is ask follow-up questions to clarify the response and elicit more details.

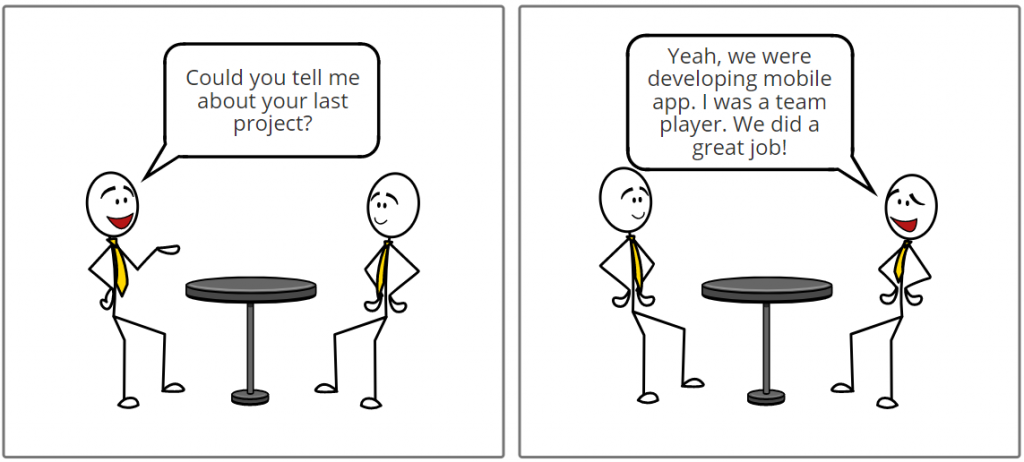

Less details, more generalities

An important part of an interview is the question about experience. It can reveal plenty of meaningful information. You should expect to hear detailed answers or a candidate’s readiness to elaborate about “when”, “where” and “how” something happened.

High performers, who actually took part in whatever is discussed, have a whole bunch of detailed stories. They are proud of their accomplishments and they are eager to share details with their listeners. Of course, it is possible that some candidates are just modest and won’t feel the need to brag. However, even if not everyone likes to boast about their success stories and achievements, they should be eager to at least share what they’ve learned.

If you really did something meaningful, which possibly required a lot of effort and wasn’t easy, wouldn’t you know all the details? Difficult projects often lead to lots of different problems to deal with. Let’s say, you built a cutting-edge application, which generated huge revenue for the company and improved the way people worked or it led to building a strong team. Wouldn’t you know all the quirks and issues that you struggled with during that task?

Speaking in generalities rather than specifics can be a reliable indicator for spotting a lie.

Look for clusters

If you want to be good at noticing fabrications, you need to be nice yet observant. You cannot be a cold-hearted interviewer whose focus is only and completely on spotting a lie. That can negatively impact the overall atmosphere and make your candidate nervous. If your respondent is frightened throughout the entire interview, it can lead to problems in spotting a lie.

I know that you probably heard that when someone is rubbing their nose, scratching their ear, fidgeting or covering their mouth a little, he must be a liar. But those signs are just shortcuts. Alone, none of these are proof of lying. Susan Carnicero advises to look for clusters instead of separate behaviors. Moreover, you need to focus on initial behavior. As Susan suggests, deceptive behavior begins within the first five seconds after a question is asked.

Conclusion

All of the above-mentioned examples comprise a list of just a few deception indicators. You should treat them more like warning signs, not a definite lie detection test. They can reveal weak points of the discussion and give you reasons to ask follow-up questions.

I recommend you read up more literature on different lie indicators. As Marc-Andre Reinhard concludes, the more you know about lie indicators, the better you are at lie detection.

References

[1] Bond, Charles & DePaulo, Bella. (2006). Accuracy of Deception Judgments. Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. 10. 214-34. 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2.

[2] Reinhard, Marc-Andre & Scharmach, Martin & Müller, Patrick. (2013). It’s not what you are, it’s what you know: Experience, beliefs, and the detection of deception in employment interviews. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 43. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2013.01011.x.

[3] Levenson, Robert & Gottman, John. (1985). Physiological and Affective Predictors of Change in Relationship Satisfaction. Journal of personality and social psychology. 49. 85-94. 10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.85.

[4] Philip Houston, Michael Floyd, Susan Carnicero, Don Tennant. (2013). Spy the Lie: Former CIA Officers Teach You How to Detect Deception. St. Martin’s Griffin.